In the second volume of his 1781 Collections for the history of Worcestershire Treadway Russell Nash included a plate of engravings depicting numismatic specimens with local links. Among them were 37 Worcestershire tokens, most originating in the private collection of ‘the Rev. Mr. Pearkes, of Worcester’. Nash’s Rev. Pearkes can be identified as John Pearkes FSA, a clergyman antiquary with strong links to Worcestershire and the surrounding counties; his ecclesiastical career included stints as curate of Kington in the 1760s and early 1770s, Prebendary of Worcester Cathedral from 1776 to 1781, and rector of Bredon and Bredon’s Norton from 1781 until his death on 27 April 1787.

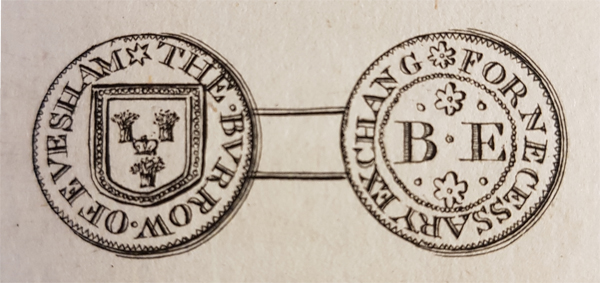

Engravings of Worcestershire tokens in Nash’s Collections; most derive from Pearkes’ collection.

During his lifetime Pearkes amassed a vast collection of books, coins, tokens, and other historical artefacts, the bulk of which were sold at two separate auctions held by John Gerard of Soho on 21-22 February and 7-8 April 1788. The corresponding sales catalogues confirm Pearke’s wide-ranging numismatic interests, which included ancient coins, contemporary medals, and plenty inbetween; at the core of his collection, however, was a ‘very curious and choice Collection of Town-Pieces and Tradesmen Tokens’, comprising more than 1,400 English, Irish, and Welsh tokens of the seventeenth century. Roughly three-quarters of these were private tokens, details of which are frustratingly absent, but the catalogue does provide information on just under 300 ‘Town-Pieces’ – halfpennies and farthings struck by civic bodies – present in his collection.

An Evesham halfpenny (Cotton 25a), almost certainly from the Pearkes collection. Engraving from Nash 1781, 91ff.

The ‘Town-Pieces’ in Pearkes’ collection have a broad national coverage, and there are only limited indications of a Worcestershire bias in the representation of issue-locations: in many respects the county’s element is pretty modest, comprising seven Evesham halfpence (Cotton 25a), two Stourbridge halfpence (Cotton 64), and a single Worcester farthing (Cotton 79). Of these specimens, however, the Evesham parcel stands out. Not only are its tokens unduly well-represented in Pearkes’ collection at the county level, they are among the most numerous in the collection as a whole – just behind Bristol, which is represented by 12 specimens, and on level pegging with Gloucester’s seven specimens. This sense of disproportionality is heightened when we consider the scale on which these tokens were produced; according to the late Robert Thompson, the number of dies used to produce Evesham’s civic tokens were considerably outranked by Gloucester and Bristol at a ratio of nearly 1:2:8.

Why, then, should Rev. Pearkes have possessed such an unusually large number of Evesham civic tokens? One possibility is that the group derives from an otherwise unrecorded hoard uncovered in the Evesham area during the eighteenth century. Circumstantial evidence suggests that this idea is not entirely far-fetched. Brick buildings in Evesham town centre testify to a substantial remodelling of the town in the eighteenth century, and it could be that a hoard of civic tokens emerged in the course of dismantling an earlier post-medieval building in this period. As a prominent local collector, Pearkes would have been attuned to any such discoveries; he certainly possessed the financial means to acquire a hoard of tokens in whole or in part. Pure speculation, of course – further archival research may furnish additional evidence supporting or challenging the theory.

Murray Andrews