On Friday 8 September I headed up to Shrewsbury to attend the Autumn Weekend of the British Association of Numismatic Societies (BANS). I’d been invited to give a lecture there by Dr Kevin Clancy, Director of the Royal Mint Museum, and on taking up his offer I opted to put together something on a local theme. Hyper-local, in fact – my presentation for the weekend was titled ‘Tokens, trade, and the seventeenth century small town: the case of Tenbury’.

The event was held at the Lion Hotel, a Grade I listed late fifteenth century coaching inn located in the heart of the town on Wyle Cop. The surroundings were well-suited for a weekend of this sort, where all speakers offered stimulating talks on coinages from across the world and of all dates – from my own perspective, particularly interesting presentations included those of Dr Martin Allen (Fitzwilliam Museum) and David Holt on the Shrewsbury mint during the middle ages and the English Civil War, and Dr Joe Bispham on the coinage of King Stephen. My own presentation took place on the Saturday morning, sandwiched between presentations on 3 Kreuzers and Islamic coins – quite a mix!

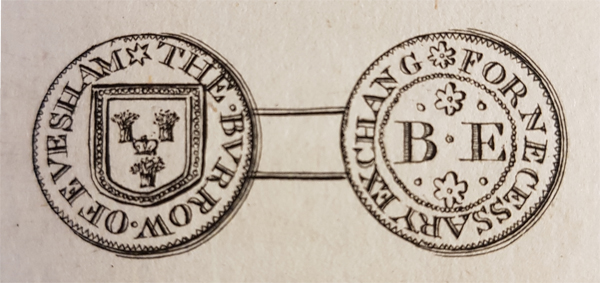

In the presentation I discussed the role of tokens in the economies of early modern small towns, using Tenbury as a case study. As followers of the Worcestershire Token Project are probably aware, there is a significant problem in token studies insofar as our understanding of the production and use of token coinages during the seventeenth century derives principally from historical evidence relating to London and the large provincial towns, yet the vast majority of the tokens we know about were issued for individuals based in small towns and large villages. We cannot simply assume that tokens were produced for the same reasons or functioned in exactly the same way in Bristol, London, or Norwich, for example, as they did in Blockley, Clifton upon Teme, or Cofton Hackett.

Taking Tenbury as a case in point, archaeological and historical sources reveal the complex tapestry of commercial activity, monetary exchange and social transactions prevalent in early modern small towns. During the seventeenth century the town hosted a weekly market and a number of seasonal fairs, where locals and outsiders traversing the twin routes from London and Montgomery to Ludlow mingled in the course of trade; it also had its share of more permanent businesses, with indentures, wills and quarter sessions recording tanners, butchers, blacksmiths, dyers, glovers, mercers, pedlars, apothecaries, victuallers and innkeepers active in the town at this period. While there was certainly a constant flow of minor transactions taking place in the town – this is no self-sufficient ‘natural economy’ – it’s likely that the greater share of commerce pursued in seventeenth century Tenbury was mid- to large-scale, involving bulk purchases and sales of livestock and agricultural produce, major sales of landed property, seasonal rent payments and the settlement of debts. In these cases the evidence suggests that payment took place using non-token media: payments in cash and in kind (e.g. cattle) appear frequently in the historical sources for this period. And even instances of petty commerce – for instance, paying for a bed at a local inn, or purchasing small amounts of goods and produce at shops on the main streets – could be cashless, conducted in credit rather than coin. In other words, the demand for ‘small change ‘ in a small town like Tenbury was probably quite a lot smaller in both absolute and relative terms than it was in a large town like Bristol or London.

All this prompts a few questions. If demand for ‘small change’ need not have been large, and might have been primarily met by credit, why then did three private issuers from the town – John Counley, Edmund Lane, and Anthony Search – bother issuing tokens at all? And, moreover, why did they do so on such a small scale – to date, each of the seven types I have seen from Tenbury issuers are represented by a single pair of dies, none of which seem to have been used to exhaustion. An additional peculiarity in Tenbury’s case is that the occupations of its token issuers do not neatly tally with those trades that we might expect to have the greatest need for ‘small change’ – for example, numerous licensed and unlicensed inns are recorded in the town during the seventeenth century, yet none seem to have issued tokens of their own.

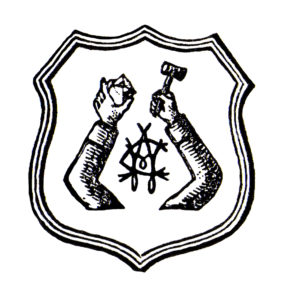

It’s possible, then, that demand for ‘small change’ may only be part of the story to tokens of this period – additional factors may also have driven the decisions of some individuals in small towns like Tenbury to commission their production. Anthony Search’s tokens of 1670, for example, note that ‘plaine dealing is best’; by stamping this slogan beside his name, perhaps this issuer was at least as concerned with promoting his credentials as a fair – and probably Quaker – businessman as he was with alleviating a demand for ‘small change’. The role of tokens as communication media are also apparent in the tokens of Edmund Lane, which usually depict a personal armorial motif – the sole examples of their kind in the entire Worcestershire series. Edmund’s name pops up from time to time in local documents of the period, where he appears as both a local notable – he served as churchwarden for the church of St Mary’s, Tenbury, in 1689, and he witnessed numerous indentures from the town and surrounding villages in the late seventeenth century – and a rentier offering cash loans across the Teme Valley. The choice to prominently display the family arms – which in any case had been created only a century earlier for his ancestor, an upwardly-mobile Warwickshire yeoman farmer named Nicholas Lane – may have functioned as part of a strategy of elite self-representation; through striking tokens of this kind he could propagate an image of himself as an established country gentleman, and thereby acquire prestige and new business. Maybe, then, private individuals in small towns did not only commission tokens to lubricate the wheels of petty commerce in their local areas; maybe they also had other goals in mind, like a desire to communicate information about themselves and their businesses to the widest possible audience.

All these ideas are very formative, and in any case the subsequent discussions provided much food for thought. I’m grateful to Kevin Clancy for inviting me to the weekend, and to all other speakers and attendees for providing such an excellent opportunity to air ideas – I look forwards to attending in the future!

Murray Andrews